Edward Baker

Sergeant Major Edward L. Baker of the Tenth United States Cavalry was born in the back of a badass horse-drawn frontier wagon while his parents were Oregon Trailing their shit out to California to start a new life. Robert E. Lee had signed the Confederate surrender at Appomattox Courthouse just seven months earlier, effectively ending the American Civil War, and Baker’s parents were pretty psyched about getting the fuck out of town and starting fresh in a new land. They packed their shit, headed out for then California Gold Country, and then popped out a son while they were fording the Platte River in the wilderness of Wyoming (pro tip: never ford the river, always pay that dude to ferry you across).

It would be a fitting start for a man who would end up spending 28 years of service to the United States Army braving some of the most dangerous, inhospitable, and unforgiving wilderness on the planet. Because whether he was dodging Apache arrows in the deserts of the American Southwest, charging enemy machine guns in Cuba, or going hand-to-hand with machete-swinging berserkers in the Philippines, this Medal of Honor badass was one of the toughest motherfuckers to ever wear the uniform – and any origin story that didn’t involve him being born in the midst of a grueling cross-country adventure just wouldn’t seem fitting for a hardass of this caliber.

We don’t know a hell of a lot about Baker’s youth in California, or how this 17 year-old adventurer even ended up at a United States Army recruiting office in Ohio in 1882. I’m going to guess it had something to do with cranking fucking sick flaming jams on the trumpet, because when he arrived in the office he was carrying a trumpet and initially enlisted as a Bugler in the Tenth U.S. Cavalry – one of the most elite, battle-hardened, and toughest military units in the Army during this time period – probably because he wanted his trumpet-playing to not only be awesome and make him some money, but that he could also inspire a thousand men to saber-charge an enemy formation of infantry just by cranking out a few notes like he meant it.

The 10th Cavalry was formed in 1866 as part of an American attempt to pacify those brutal, bloodthirsty, savage Native American tribes that were scalping settlers, attacking Army posts, and burning villages across the West for no good reason except that we technically were stealing their land and building houses on it and then killing them when they complained. Known as the “Buffalo Soldiers”, the unit consisted entirely of African-American soldiers and NCOs commanded by white officers. Think of it like Glory mixed with Custer’s Last Stand. Dressed in blue uniforms and packing badass cowboy six-shooters, cavalry sabers, and lever-action Winchester rifles, the men of the Tenth patrolled the American West on horseback protecting American settlers, fighting uprisings from the Cheyenne, Kiowa, and Commanche, and even occasionally taking down bands of gunslinging bandits holed up in cool cave networks that looked like something straight out of a cheesy Western film. It was so fucking awesome I can barely stand it.

There are five theories about why the 9th and 10th were called “Buffalo Soldiers”:

1. Black peoples’ hair made the Indians think of a buffalo’s fur.

2. The Indians believed black people were imbued with the spirt of buffalos.

3. It’s because 9th and 10th Cavalry wore buffalo hide capes in the winter to keep warm.

4. The 9th and 10th fought with the ferocity and tenacity of a buffalo defending its herd.

5. The Indians thought the 9th and 10th Cavalry were from Buffalo, New York.

Ok, I made that last one up.

By 1885, Trooper Baker was a three year veteran in the Tenth, and by this point he’d pretty much traded his trumpet for a Winchester and a .45. His unit was transferred from the Great Plains down to the Rio Grande frontier, where there was a dude named Geronimo causing all kinds of shit and wrecking balls with a rampaging army of hardcore-as-fuck Apache warriors. Largely believed by 1950s Cowboy movie writers to be the most ferocious of all the Native warrior tribes, the Apache were a tenacious group of hardened warriors who packed a ton of firepower and were experts in the art of the ambush. Baker and his men were part of the crew that went to hunt down Geronimo and his band – they weren’t involved with his capture, but that was only because they were in the middle of a hardcore canyon shootout with a group of Geronimo’s loyal Apache followers at the time.

After fighting in Arizona was over, Baker and the Tenth returned to Montana, where they got a new commanding officer – Black Jack Pershing. The man who would command the U.S. Army in World War I, and go down as among the most hardcore badasses in U.S military history.

Baker’s bravery in the face of gunfire, tomahawks, arrows, and other horrible shit quickly earned him a reputation as being one of the baddest dudes in the Tenth Cavalry, and by 1898 he had been promoted to the rank of Sergeant-Major, making him one of the senior NCOs in the unit. I have no evidence of this, but I like to think of him as like a cowboy version of the Sergeant Johnson from Halo.

Baker and the Tenth’s next adventure would take them to Cuba, where a huge war had just broken out between the United States and Spain. Cuba was still a Spanish colony in 1898 but the Cubans didn’t like being ruled by Spain, so America helped them in their struggle to overthrow the Spanish government because this is America and we believe in freedom, democracy, liberty, justice, and oh yeah maybe we can also steal the Philippines from Spain while we’re at it and start building our own Empire shhh don’t tell anyone.

If you think it’s a little weird that an Indian-fighting frontier regiment like the Tenth Cavalry would end up being called in to a front-line combat role against a modernized European army is a little weird, that’s because it kind of totally is. And there’s a fucking weird story behind why they were there.

Most of Cuba at this time was oppressive jungle, plagued with overwhelming heat, rampant disease, and oppressive humidity. Within days of landing on the island, American forces were overcome with malaria, yellow fever, dysentery, and other horrible illnesses. It was so bad that at one point some regiments fucking temporarily suspended guard duty operations because they didn’t have enough healthy men who weren’t barfing or crapping themselves within an inch of their lives.

To combat this, the American Army sent…. all of the black units in the military. Because they believed – I kid you not – that black people were immune to tropical diseases. I guess because their grandparents and great-grandparents were from a tropical climate? Who knows. Either way, it didn’t work, and it shouldn’t surprise you to learn that black people can also get sick when they are bitten by a malaria-infected mosquito.

Well, one unforeseen consequence of this “it would actually be kind of hilarious if it wasn’t so overtly racist” case of terrible 19th century science is that the single most climactic American battle since the Civil War was fought by nearly 2,000 African-American soldiers who had been forged into a ferocious fighting machine by decades of combat against the toughest outlaws and Native American warriors in the Old West. And this was a big fucking deal, considering that the Battle of San Juan Hill took place just 20 years after the end of the Civil War (fun fact, the commander of the American cavalry at the battle had been a Confederate General – when Joseph Wheeler saw his troops winning the fight, he hilariously screamed “Come on boys, we got the Yankees on the run!” before having to be politely informed by an adjutant that we, in fact, were the Yankees). The heroism of the 9th and 10th Cavalry at the fight would go a long way towards breaking color barriers in the U.S. Army.

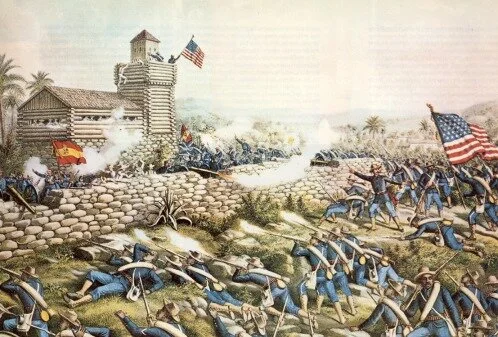

But, I’m getting ahead of myself. Let’s start at the beginning – dawn on July 1, 1898. Edward L. Baker, Sergeant-Major of the 10th U.S. Cavalry, stood at the head of his unit, staring up at a heavily-defended Spanish position bristling with barbed wire, trenches, bolt-action Mauser rifles, and belt-fed Maxim heavy machine guns. On his left flank was the Ninth U.S. Cavalry, another unit of Buffalo Soldiers. On his right, was the First Volunteer Cavalry Regiment – led by Lieutenant-Colonel Theodore Motherfuckin’ Roosevelt and known as “Roosevelt’s Rough Riders”. Further down the line were a couple infantry brigades, including an all-black Brigade consisting of the U.S. 24th and 25th Infantry Regiments.

Their objective was simple – storm out of the jungle, run on foot across open ground, cross a fucking river, scramble up a hill through a couple of seven-foot-tall barbed wire walls, cross a half-mile of enemy trenches, and attack the hardened, sand-bagged, machine-gun-entrenched brick fortress at the top of San Juan Hill.

No problem.

Artillery rang out from both sides as Krupp guns and other heavy cannons started lobbing shells back and forth across the landscape. Towering piles of dirt were kicked hundreds of feet in the air, machine gun bullets whizzed through the jungle brush, and then, suddenly, a screaming horde of American soldiers came racing full-speed out of the jungle on a single-minded mission to capture that fucking hill or die trying. They raced through the ground, taking horrific casualties, but Baker screamed for his men to stay in line, keep your ranks, put fire out there and don’t lose your cool. Down the line, the African-American Infantry Brigade took the brunt of the Spanish machine gun fire, losing four commanders in under 11 minutes, but still the attack pushed on. When the army reached the river, men swam or waded across as best they could, then scrambled quickly up the muddy banks on the far side of the river bed in their assault on the hill.

Despite taking heavy casualties in the attack, the Americans regrouped at the base of the hill and prepared for the final push, keeping their heads down as Spanish machine gun and rifle fire cracked endlessly overhead.

Then, from the river, Sergeant-Major Baker heard a horrible scream – one of his men, his brothers, had taken a bullet while crossing the river, and his wound was so severe he couldn’t stand or swim. One of the men Baker had served with for years was about to drown in six feet of river water.

Fuck that.

Despite men taking hits and bullets and explosions all around, Sergeant-Major Edward L. Baker left cover, raced back to the river, jumped in, and grabbed his man. With Spanish snipers taking shots at him from the trenches and the jungle on his flank, Baker grabbed the wounded man, pulled him from the river, dragged him up that fucking muddy slope through sheer force of will alone, and got him in to cover. Nobody could believe it. Even Teddy Roosevelt was impressed – he would later write about the amazing bravery and heroism he witnessed first-hand by the Tenth Cavalry in the battle.

This rescue was the thing that would earn Baker his Medal of Honor, but for this tough-as-nails Sergeant the hard part was just getting started. Moments after getting back into cover, General Henry S. Hawkins rode out on his horse, turned his back to the enemy guns, and shouted – “Boys, the time has come. Every man who loves his country, forward and follow me!”

“When that pack of demons swept forward the Spaniards stood as long as mortals could stand,

then quit their trenches and retreated… it now seems almost impossible that

civilized men could so recklessly destroy each other.”

-- Cpl. John Conn, 24th U.S. Infantry

With a scream, the American lines rose up, unloaded some covering fire, and hurled themselves at the enemy. The Spanish unleashed hell, drilling accurate fire into the U.S. lines, but no force on Earth was going to stop this attack. Teddy Roosevelt, Edward Baker, the Tenth Cavalry, and the rest of the American brigades charged on, leaping in to the Spanish trenches with six-shooters, swords, bayonets, and anything else they could use to kill the enemy. The Spanish lines broke and retreated, pursued closely by the Tenth Cavalry.

The Battle of San Juan Hill cost the lives of over 200 American soldiers, but it was a decisive victory that ended the Spanish-American War. Newspaper correspondents who witnessed the event wrote glowing praise for the soldiers who fought there, and four men from the Tenth Cavalry – including Edward L. Baker – would receive the Medal of Honor for heroism in the war. He was promoted to Lieutenant after the battle, making him one of the first black officers in the history of the United States Army.

“Only annihilation could drive them back; the Spaniards could not.”

- The New York Sun

After the war the United States seized control of the Philippines from Spain, which pissed off the Filipinos (who immediately rebelled), and once again it was time to send in the masters of guerilla warfare to come save the day. The Tenth Cavalry and Lieutenant Edward Baker were sent to Manila, where they battled the Philippine Insurrection and did combat with ferocious hardcore jungle warriors who were packing badass slasher-movie-style machetes and were so badass in their berzerking that there are reports of these guys getting shot twice with a .38 and not even breaking stride in their charge. I wish I had more details about Baker’s service there, but we do know that after the Tenth Cavalry left the Philippines, Baker stayed behind and became a training officer for the Philippine Scouts – a tough group of Filipino warriors who were trained to help fight against the rebellion . So that’s cool.

Edward L. Baker retired with the rank of Captain after 28 hard years of combat experience in one of the United States’ most famous cavalry regiments. He lived through the end of the Old West, witnessed the beginnings of mechanized, World War I-style combat, and fought everyone from Apache riflemen to Spanish infantry to Filipino guerillas. After retirement, he went home to Los Angeles, where he died in 1913 at the age of just 48. His grandson, Dexter Gordon, was a famous jazz saxophonist who played jams with Louie Armstrong and Dizzy Gillespie, and is the godfather of Lars Ulrich from Metallica. Don’t tread on me, indeed.

Sources:

Hanna, Charles W. African American Recipients of the Medal of Honor. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2002.

Sutherland, Jonathan. African Americans at War. Vol. 1. Santa Barbara, ABC-CLIO, 2004.

http://www.blackpast.org/aaw/10th-cavalry-regiment-1866-1944