Oscar Charleston

"There were three things Oscar Charleston excelled at on the field: hitting, fielding, and fighting. He loved all three, and it’s a toss-up which he was best at."

One of the infamous "Four Bad Men" of Negro League Baseball, Oscar Charleston was a fastball-obliterating, hot-tempered, pitcher-terrifying superstar who, in addition to being one of the greatest and most ruthlessly-efficient five-tool players to ever live, also found time to serve the United States in three armed conflicts, helped scout Jackie Robinson into the Major Leagues, and survived a parking lot brawl against a horde of pissed-off machete-wielding Cubans while armed with nothing more than his own two fists and an uncontrollable urge to punch the hell out of anyone that came within arm's reach.

Born on Indianapolis's east side in 1896, Oscar Charleston grew up in a big family (some sources say 6 kids, others 10) of seriously tough bastards. His dad was a construction worker, and his brothers were all successful boxers, but while Oscar certainly developed an early interest in connecting his fist to other peoples' faces as forcefully as possible, he didn't really feel much like sticking around his hometown, so at the age of 15 he quit school, lied about his age to the local Army recruiter, joined the service, and was shipped out to the Philippines as part of the U.S. 24th Infantry Regiment. From 1910 to 1915 he was stationed outside Manila as part of the post-Philippines War American occupation, where he could look forward to occasionally having to come face-to-face with psychotically-badass groups of bolo-knife-wielding Filipino berserkers who wanted nothing more than to disembowel every American soldier they could find until the U.S. decided to get the hell out of their country. When he wasn't trying to maintain order or keep his intestines in one piece, Oscar Charleston joined the U.S. Army baseball team, where he overcame segregation to become the only black player in the Manila League baseball association. Oh and while he was at it he set an Army record by running the 220-yard dash in 23 seconds, which is pretty fast considering that the 1912 Olympic gold medal time in the 200-meter dash (roughly 218 yards) was 22 seconds.

"Some people asked me, 'Why are you playing so close to the right-field foul line?'

What they didn't know was that Charleston covered all three fields, and my responsibility was to

make sure of balls down the line and those in foul territory."

-Dave Malarcher

Charleston came back to the States in 1915 and tried out for his hometown team, the Indianapolis ABCs, an all-black semi-pro "barnstorming" baseball club that pre-dated the Negro Leagues by five years, and that made a living basically by driving from city to city in a crappy old bus playing against any moderately-organized team that would share a field with them. Charleston hit a home run in his first game, an exhibition matchup against an all-white team of retired ex-major leaguers, thus kicking off a 40-year baseball career that would take him from pre-Negro Leagues to post-Jackie Robinson.

Of course, what makes Charleston badass isn't just that he was an incredible baseball player – it's that this guy was as ball-crushingly tough as they come, and so utterly fearless that nobody messed with him and lived to tell the tale. Described as having steel-gray "gunfighter eyes", and a pair of hands so strong they could rip the cover off a baseball, Charleston refused to ever back down for any reason, even when it was probably a really good idea to do so, and his hot temper and penchant for face-punching insanity typically got him into a hell of a lot of trouble pretty much all the time. In his rookie season, he was suspended for a couple games for "insubordination" (this is code for "getting into a damned fistfight with his manager) and then, a few games after he came back, he came to the defense of his second baseman after a hard play at second, and ended up getting completely carried away, punching an ump unconscious with one swing, and causing a brawl that emptied both benches, the grandstands, and the local police station. As the run-of-the-mill baseball fight became a city-wide riot and cops started rolling in with billy clubs, tear gas, and revolvers, Charleston ran for it, evaded capture for a while, then ended up getting tossed in jail while still in his baseball uniform. Once he'd cooled off a little he wrote a very nice apology letter to the KO'ed ump, who agreed not to press charges, and the next morning Charleston was on the team bus headed to the next town. He'd go on to hit .360 in the Black World Series and lead his team to the championship. He took a brief one-year hiatus from baseball in 1918 to go serve as a Corporal in World War I (no big deal I guess), but by 1920, when the Indianapolis ABCs became a charter member of the Negro National League, Oscar Charleston was already the NNL's biggest star.

"Charleston could hit the ball a mile. He didn't have a weakness. When he came up,

we just threw it and hoped like hell he wouldn't get a hold of one and send it out of the park."

- Dizzy Dean, Hall of Fame pitcher

I won't get too much into the stats and stuff, except to say that Oscar Charleston was, without question, the greatest five-tool threat the Negro Leagues ever produced. Standing six feet tall and weighing two hundred pounds, Charleston could hit for contact and power, but "The Hoosier Comet" could also steal bases at will and covered so much ground in the outfield that many hitters were convinced this guy could legitimately run faster than the ball. He could hit fastballs, curveballs, trick pitches, lefties, righties, and umpires, compiling nine seasons with an average over .350 (one pitcher quipped that the only way to get a pitch past him was to sneak one in while he was arguing with the ump), and anything he made contact with went a long, long way. In 60 games in 1921 he hit a mind-blowing .446, and led the league in doubles, triples, home runs, and stolen bases (i.e., every single damn thing they keep a stat for). A lifetime .348 hitter, Charleston finished his career in the Negro Leagues' top five in every major all-time statistical category, including his record as the League's all-time leader in stolen bases. This was a guy who would club a 450-foot bomb over the center field fence and then run down a fly ball and make an obscene diving barehanded catch at the bottom of that same inning. During one exhibition series against the MLB's St. Louis Cardinals – a series where he faced Hall of Fame big-league pitchers like Bob Feller and Dizzy Dean – Charleston hit 5 homers in 5 games, batted .458, and on three occasions he knocked a single, yelled to the pitcher that he was going to steal second on the next pitch, and then did it. And while there's sadly no footage of him in action, every sports writer who ever saw this guy play said that it was unlike anything they'd ever seen before – a hot-tempered, two-fisted asskicker who could hit like Babe Ruth, field like Tris Speaker, and run the bases like Ty Cobb.

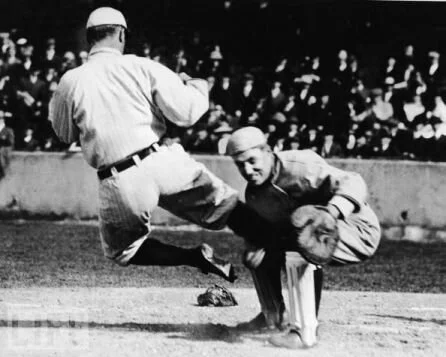

Oh yeah, and if that last part doesn't mean much to you, here's a picture of Ty Cobb running the base paths. He ran angry. So did Charleston. There's more than one Negro League third baseman who boasted about the permanent scars on his arms and legs he'd earned the hard way by standing in front of two hundred pounds of Oscar Charleston hurtling towards him cleats-first like a gigantic barrel-chested freight train with spikes attached to the end of it.

"This is a game you're supposed to play and you're supposed to play it rough and you ain't got no business complaining."

Of course, unlike Cobb, who is pretty much notorious for being an all-around complete bastard, it is worth noting that Oscar Charleston is almost universally-described as a good man who was kind to others off the field, and that it was just his ultra-competitive nature and unwillingness to back down from any challenge that made him a demon from hell on it. Regardless, the stories about his exploits are pretty much legendary. I mean, no joke, this guy was so intense on the field that the City of Indianapolis banned inter-racial baseball games because Oscar Charleston had started a bench-clearing brawl during an exhibition against the Cardinals' farm team because he thought they were beaning his teammates on purpose.

During the Negro League off-season Charleston kept his skills sharp by participating in Winter League Ball in Cuba every year from 1919 to 1928 (interestingly he's the Cuban League's all-time leader in batting average and stolen bases and was inducted into the Cuban Baseball Hall of Fame in 1997), but apparently the hot weather just exacerbated Charleston's temper. During one game, Charleston chased a deep ball all the way to the fence, ran two steps up the wall Bo Jackson-style and snagged the ball just in time to steal a home run away from the hitter, only to have some Cuban Steve Bartman jackass pull the ball right out of his glove. Charleston, slightly enraged over this, then pulled the fan over the wall onto the field and slugged him in the gob. After the game, Charleston was making his way to the team bus, when the fan and a couple of his closest buddies confronted him armed with machetes and prepared to hack the Center Fielder apart Jason Voorhees style. Charleston, no stranger to battling machete-swinging assailants, fought them off with his fists, dropping two of them before the cops showed up and broke it up.

A few years later, Charleston was out in Center Field when one of the Cuban team players came in hard on a double play ball and knocked Charleston's Second Baseman unconscious with a vicious tackle. Charleston, never one to show much restraint on the field, ran in and clocked the dude, sending him sprawling and kicking off another melee. Unfortunately for Charleston, the unconscious baserunner just so happened to be the brother of a member of the Cuban Army, who had been assigned as security for the game, and no sooner had Charleston landed his swing than a dozen or so fully-armed Cuban military troops were vaulting over the wall after him. Charleston didn't blink. According to the story I read, "He took them out by himself, one after the other, until reinforcements arrived."

On yet another occasion, Charleston and a couple of his teammates were leaving a game in Florida when they were confronted in the parking lot by a band of white-robed Klu Klux Klansmen. While the two guys with Charleston were obviously a little shaken about coming face-to-face with angry KKK bastards, Charleston just got pissed. He walked straight up to their leader, ripped the hood off the guy's head, and told him and his buddies to piss off.

They did.

After getting pissed and punching his team owner in the face in a clubhouse argument, Oscar Charleston was traded to the Homestead Grays in 1930, where he was made player-manager of a stacked lineup, hit leadoff, and ended up taking his team to the Negro League Championship. He won the title for the Grays again in 1931, and in 1932 he moved to the Pittsburgh Crawfords, where he hit cleanup, batted .363, and managed a team of five future Hall of Famers to a 99-36 record and his third consecutive Negro League Championship. From 1932-1936 he continued to hold a .340+ average despite being almost 40 years old, managed his team to yet another Negro League World Series championship in 1935, and developed guys like Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson, and Cool Papa Bell into Hall of Fame-caliber talent.

Oscar Charleston took yet another break from baseball, this time to work in the Pennsylvania Quartermaster's Department and provide logistical support to American troops fighting during World War II. After the war Charleston was hired by Branch Rickey to work with the Brooklyn Brown Bombers, a farm club associated with the Dodgers, where he was charged with scouting talent to help break the race barrier in Major League Baseball. Rickey knew that nobody knew the Negro Leagues like Oscar Charleston (who'd had roughly 30 years experience at this point), and with Charleston's help Rickey was able to bring guys like Jackie Robinson and Roy Campanella into the pros, integrating Major League Baseball for the first time.

Once black players were in the Majors, the Negro Leagues began to fade away, but that didn't stop Oscar Charleston from doing what he loved. He got back into managing, winning two more championships with the Indianapolis Clowns – one in 1950 and one in 1954. Four months after winning what was (at least) his seventh championship, Oscar Charleston suffered a stroke and died in his home at the age of 57.

He was inducted in the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1976, the first person from Indianapolis and only the second Negro League player to make the Hall (he'd managed the first one, Josh Gibson).

"He wanted to know, was you a crybaby or was you a man. He was that type of manager. He was nice to talk to, he just didn't back down from nobody. He knew baseball."

Links:

ESPN

NegroLeagueBaseball.com

NLB Museum

Baseball-Reference

Biography

Answers.com

Sources:

DeBono, Paul. The Indianapolis ABC's. McFarland, 2007.

Holway, John and Frank Ceresi. Voices from the Great Black Baseball Leagues. Courier Dover, 2010.

Peterson, Robert. Only the Ball Was White. Oxford Univ. Press, 1970.

Porter, David L. African-American Sports Greats. ABC-CLIO, 1995.

Whirty, Ryan. "Forgotten Son." Indianapolis Monthly. October 2004.