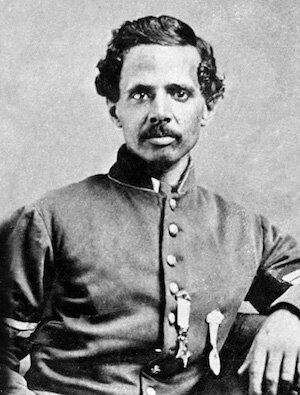

Powhatan Beaty

Powerfully built, rugged and strong in his general appearance, he looked every inch a Roman gladiator. The audience leaned forward and eagerly listened to catch every word of his impassioned delivery, and when he finished they fell back in their seats with a sigh of relief that plainly expressed how they had been affected.

Mr. Beaty is indeed a grand artist and has wisely selected the tragic muse for the shrine of his artistic devotion.

Powhatan Beatty was a hardcore dude with a badass Action Hero name who was born into slavery in the heart of the Confederacy, escaped to freedom, received the Medal of Honor for heroic actions undertaken in a bayonet charge to liberate his hometown, survived thirteen Civil War engagements, and then went on to become a successful playwright and one of the first black actors to ever perform Shakespeare on stage in the United States. He was a guy who came from the humblest beginnings imaginable, refused to give up, surrender, or accept defeat even when literally confronted by certain death at every side, and consistently persevered against all odds to conquer and achieve the highest honors at pretty much everything he ever set his mind to. He's basically a 19th-century version of Bill Hader's Barry mixed in with a bit of Django, Morgan Freeman's character in Glory, and Actual Morgan Freeman in Real Life, and then you just mash that all together and shoot it bayonet-first out of a goddamn howitzer onto a stage at your local community theater. And, if that isn't getting you at least a little bit pumped up, then it's probably time to get off decaf and stop grinding xanax into your chamomile.

Beaty was born into slavery on a farm outside Richmond, Virginia on October 8, 1837. Whether he fled, or was freed, or his family moved him to Ohio is a bit of a mystery, but we do know for sure that he ended up in Cincinnati at some point before 1849, at which time he was granted his freedom. Now, Cincinnati was the sixth most-populous city in America in the 1850s (it's currently sitting at 64), but as much as those Ohioans love to talk about how they produced Grant and Sherman that doesn't necessarily mean that Cincy was a really amazing utopia for African-American people duiring this point in history – Black citizens of Cincinnati were free, but they still couldn't vote, weren't allowed to testify against white people in court, and (probably as a result of the later) were attacked in the streets and had their places of business vandalized with a pretty alarming frequency. Still, Beaty made it work, and got a job working as a cabinet maker and lathe operator while going to school on the side to study his first and truest love – acting. He loved plays and performance, appeared in hundreds of local shows, and basically just made cabinets and worked construction to pay the bills while he honed his true craft in the evenings.

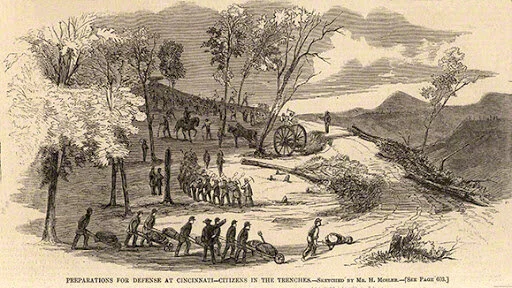

Well, shit got kind of nuts in America when the Civil War started in 1861, and the war really hit home in Cincinnati in September of 1862 when Confederate forces under the command of Gen. Kirby Smith crushed the Union forces at the Battle of Richmond, Kentucky. This miserable defeat put the Rebels just 100 miles from Cincy, with very little in terms of Union defenses between the city and the enemy, and not only was there a very imminent threat of attack by Confederate cavalry raiders like John Hunt Morgan and Bloody Bill Anderson, but there was also a genuine fear that the entire Rebel army was going to march north and put the town under siege.

The people of Cincinnati were threatened, and it was up to the citizens of the city to prepare the defenses for an attack that, in their minds, could have come any minute. African-Americans, including Powhatan Beaty, volunteered for service to assist in the fortifications. They were denied, because the city didn't want black soldiers.

Then, of course, a few weeks later, the Cincinnati police department changed their minds, rounded up all the city's black people at gunpoint, and forced them to go 15 miles out of town and dig trenches, rifle pits, and fortifications.

Yep, awesome. Just… great.

The Black Brigade of Cincinnati might have been formed under some pretty unsavory conditions, but it does hold one interesting distinction – it was the first unit of African-Americans used primarily for military service in the history of the United States Army. Powhatan Beaty was there, staring the enemy in the face, armed only with a shovel, digging fortifications and defenses to protect his city from attack by the enemy. He knew that the city falling would not be great for him or the other men of the Black Brigade, and was determined to do his part to ensure the safety of the Ohio-Kentucky border. And, it worked. The Confederate attack never came, and the city was untouched throughout the entire war.

Nine months later, however, Beaty took a more direct path of facing the enemy – this time, instead of digging holes in the ground, he was going to face his foes head-on, with a weapon in his hands and a bayonet gleaming at the tip of his rifle.

On June 7, 1863, twenty-five year old Powhatan Beaty enlisted in the United States Army.

Following the Emancipation Proclamation in January of '63, Northern states started organizing African-American infantry units – units like the famous 54th Massachusetts that you probably know best from the movie Glory – and the second Beaty heard about that shit, he was in. He helped recruit 47 men from Cincinnati, many of them veterans of the Black Brigade, and together they reported to the State House in Columbus requesting transfer to Boston to join the 54th Massachusetts. The Governor of Ohio, David Tod, was told that the 54th was at full strength and didn't need more recruits, so Governor Tod instead petitioned the Army for the right to raise a regiment of Ohioans to join the war effort. Permission was granted, Beaty was appointed First Sergeant in the 127th Ohio Volunteer Infantry. The fact that this guy went from E-1 to E-8 in just two days should give you some indication of how respected this guy was by his peers and his men… and you'll see why as we go forward.

After three months of recruiting and training in Columbus and at Camp Delaware, the State of Ohio had raised two regiments of Volunteer Infantry, and in November of 1863, First Sergeant Powhatan Beaty marched off to war.

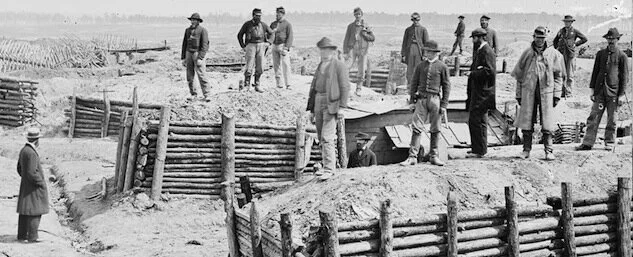

The 127th Ohio (which by now had been redesignated the 5th Regiment United States Colored Infantry) first spent some time in North Carolina and Yorktown but was eventually attached to the command of Major General Benjamin Butler and thrown into the Siege of Petersburg — the nine-month siege of Richmond's last major supply depot. This was a brutal, bloody, extended engagement that is famous among military historians for being the first real appearance of Trench Warfare on the battlefield, as both sides dug these huge-ass entrenchments and spent most of the fighting just lobbing artillery back and forth and getting their guys massacred in human wave attacks. Like, if you wanted to pick an exact moment in Military History where tactics transitioned from those big lines of riflemen maneuvering around big open fields (the kind of war you see in Napoleonic times and the American Revolution) into those bombed-out barren hellscapes of World War I trench warfare, the Siege of Petersburg is that moment. The fighting was tough, brutal, and ferocious – the Rebels were clinging to the last bastion of the Confederacy, and the Union was hurling every available man at their hardened defenses with minimal strategy and horrific human loss.

Union siege works at Petersburg.

Powhatan Beatty and the 5th USCI were at the Battle of the Crater in July 1864 – a truly bizarre engagement where Union sappers dug a big tunnel under the siege lines and set off a few thousand pounds of TNT that blew a massive crater into the earth that was way bigger than anything anyone was expecting and was so bonkers that they named the ensuing gunfight after it – but their Finest Hour came in September when they were called into action at the Battle for New Market Heights.

Beaty and the 5th were ordered to charge uphill head-on into heavily-entrenched earthworks that were tenaciously defended by a bunch of pissed-off Texans from the 1st and 5th Texas, assisted by cav from the 24th Virginia. And, as you know, I make a lot of "Don't Mess with Texas" jokes on this site but, dude, it's for real, and being ordered to make a bunch of angry Texans even more pissed is really not a great career move for people who don't want to have their balls removed with a Bowie knife. But Beaty got the call, and, at 5 AM on the morning of September 29, 1864, he went over the top at the head of Company G, leading his men through the darkness into battle.

The attack was meant to be a surprise, so the 700 men of the 5th USCI were ordered to fix bayonets, load powder and shot, but leave the percussion caps off their guns to prevent a rifle going off by accident and alerting the enemy to their position. Now, without getting too technical, I just want to point out that you can almost certainly reload a modern pistol magazine quicker than you could dig out a cap from your cap box and pop it on your rifle, so for all intents and purposes the Fifth was attacking in the darkness with unloaded weapons.

Still, bravely, fearlessly, they moved forward, staying low and quiet until they were close enough that the enemy spotted them and opened fire.

The 5th loaded their rifles, fired, and charged.

The Texans returned fire with brutal efficiency, blasting point-blank into the Union ranks with grapeshot from cannons and pouring brutal rifle and pistol fire into the attacking Union forces. The first several salvos, unleased with murderous accuracy from well-entrenched fortifications, were absolutely brutal, and cut hard into the Union lines, shredding them apart. First Sergeant Beaty had a bullet go through his hat, and had a button shot off, and had a hole blown through his canteen, yet still he urged his men onwards, head-on into a hail of gunfire, with his troops dying left and right around him.

Soon, however, the attack faltered, as the casualties became too much to bear – in the span of just a few minutes, the 700 men of the Fifth USCI had already suffered 365 killed in action, with many more wounded. All of their white officers – every single one of them, including the unit’s commander, were dead or wounded on the battlefield. With no one to lead them, the Fifth broke, fell back, and retreated towards friendly lines.

Then, through the gunsmoke, haze, and fog of war, Beaty noticed something terrible. The flag bearer for the Fifth had been shot while retreating and the colors now lay abandoned a full 200 yards from the withdrawing Union forces.

Now, it stands to be mentioned that having your flag captured in the Civil War was a mortal sin. There was no greater dishonor for a unit than to lose its flag.

And there was no fucking way Powhatan Beaty was going to allow that to happen.

First Sergeant Beaty, now the ranking officer of the entire 5th United States Colored Infantry Regiment, rallied his men, screamed above the din of battle for them to turn to fight, and then personally charged through 200 yards of non-stop gunfire to recover his unit’s fallen flag.

Then, when he got it, he picked it up, waved it aloft, and then just kept on running forward.

His men followed. And they didn't stop until they'd hurled themselves bayonet-first into the defenders on New Market Heights.

Ferocious hand-to-hand fighting ensued, as the men of the Fifth fought through their exhaustion and injuries and battled with fists, teeth, knives, bayonets, and rifle butts – fistfighting and meleeing the enemy with every last drop of energy in their reserves. The Texans fought back with equal fury, but, when the smoke cleared and the fighting finally subsided, the Rebels had been driven from the works and First Sergeant Powhatan Beaty triumphantly planted the Stars and Stripes on the fortress walls at New Market Heights. Of the 91 officers and enlisted men who had entered the battle with Company G, only 16 remained at the end of the fighting. Powhatan Beaty was one of them.

But he still wasn’t done. Because the Confederates reorganized and counterattacked the following day, and Powhatan Beaty once again rallied his men to fight off a ferocious rebel assault.

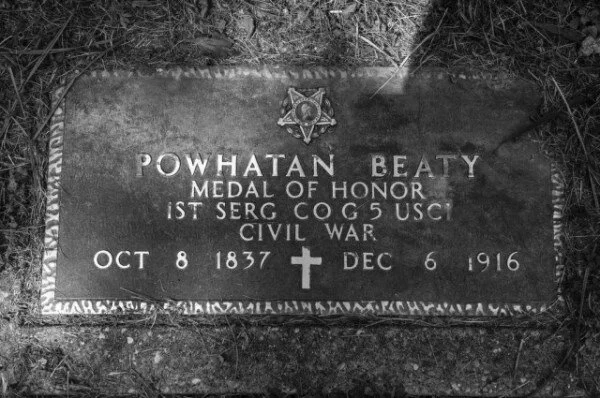

For his actions in rallying his men, assuming command, of a desperate and hopeless situation, and then valiantly leading a balls-out bayonet attack that won the day and overran the enemy, Powhatan Beaty was awarded the Medal of Honor and was granted a brevet battlefield promotion to Lieutenant. The US Army rejected the promotion, on the grounds that the US Army did not allow black officers in its ranks, but Beaty’s commanding officer just kept promoting the dude to Lieutenant every couple of months anyway.

Beaty went on to lead his company into the Second Battle of Fair Oaks in October, then, after that, he participated in the attack on Fort Fisher -- the "Gibraltar of the South". Fisher was the fortress that guarded the mouth of the Cape Fear River in North Carolina, and at this point it was the last major Confederate coastal stronghold of the war. In an assault that very closely resembled the attack of the 54th Massachusetts on Fort Wagner at the end of Glory, Powhatan Beaty and the 5th USCI attacked Fort Fisher, were defeated, but then regrouped, attacked it again a week later, and seized it.

A few months later, the Confederacy collapsed, and Powhatan Beaty returned home a war hero — a hardened veteran of thirteen bloody battles and a Medal of Honor recipient who had fought heroically and help overthrow the institution of slavery forever.

The seccond assault on Fort Fisher.

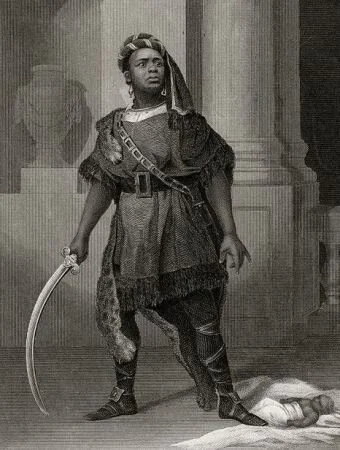

After the war, Beaty returned home, got married, and raised a family. Beaty continued doing the carpentry thing, but he also wrote plays, acted in shows, and soon became a local celebrity and a well-known hero of Cincinnati’s performing arts scene. He portrayed guys like Spartacus and Othello for black and white audiences alike, and received almost universal praise for his powerful deliveries and impressive acting chops. One local paper even mentioned that at one show a group of rowdy white dudes showed up to heckle this guy, but after just a few minutes they shut the fuck up and were just as enraptured by the performance as everyone else in the audience.

This is Ira Aldridge, the first Black actor to perform Shakespeare in America, but you get the idea.

Beaty's big break onto the national scene came in 1884, when the most famous black actress in America, Henrietta Vinton Davis, came to town as part of some big tour she was doing. She did a few shows with Beaty and was so impressed by his talent that she decided to bring him along with her for the rest of the tour, and they did shows in New York, Philly, DC, and several other places along the Eastern seaboard. In May of 1884, he even performed a sold-out show at Ford's Opera House in Washington DC in front of guys like Frederick Douglass and a bunch of sitting U.S. Senators and Congressmen. Davis and Beaty performed a few Shakepearean scenes, and they received rousing ovations for their work.

Powhatan Beaty continued doing shows and performances, lived a long and happy life, watched his son grow up to be one of Ohio’s first black US District Attorneys, and died in December of 1916 at the age of 79, one of the true unsung heroes not only of the Civil War, but in African-American history.

Links:

Books:

Hanna, Charles W. African American Recipients of the Medal of Honor. United States: McFarland, Incorporated, Publishers, 2015.

Sutherland, Jonathan. African Americans at War: An Encyclopedia. United Kingdom: ABC-CLIO, 2004.

Williams, George Washington. A History of the Negro Troops in the War of the Rebellion. United States: Harper & Bros., 1888.